STEINWAY & SONS GRAND PIANO 15150 (NEW YORK, 1867)

|

Historic aspects

This Steinway & Sons 1867 grand piano, n. 15150, of 220 cm length, with a compass of seven octaves (AAA, a’’’’), constitutes an example of the first piano typology of the New York based piano industry, after the application of the cross stringing. Such a typology which is characterized by a very pure and warm sonority as well as by a very ample dynamic and timbre range, was produced during a rather short period, from about 1859 to 1871. It was then modified according to patents of the Duplex Scale and of the Capo d'Astro bar, elaborated by Theodore Steinway himself and by the acoustic physicist L.F. von Helmoltz. Such patents defined a construction model which then became the prototype of the modern piano, opening the path to a different tending concept of piano, partially divergent from the ideal romanticism. A concept which was later developed and interpreted by the composers of the 1900. Theodore Steinway obtained 45 patents during the period from 1868 to 1885, including the ones mentioned above. It was reported however, that the workers of Steinway & Sons sometimes tried to advise him not to perform further modifications on the typology here described, on the assumption that it was already perfect.

This grand piano was made in New York in 1867, the same year in which the Steinway firm obtained undisputed success over its European contemporary pianos at the Paris Expo for all three piano typologies: grand, upright and square pianos. The judging panel also included famous musicologists of the time, such as François J. Fétis and Edward Hanslick.

|

This instrument is strung with crossed strings, and as written on its frame, the patent for this was registered by Henri Steinway Jr. in 1859. This method of stringing gives the instrument some of the specific characteristics of its sound production, which amazed the international public and music critics at the time.

The moving of the bridges towards the centre of the soundboard increased the purity and the roundness of the transients, contributing to the make up of the typical and well-known sound of the Steinways that is almost “lustrous”. The sound decay parameters (especially in the middle and the high texture), improved above the standard that could generally be found in the best instruments from the most prestigious piano makers in Europe at that time.

“With regard to their expression, delicate shading, and variety of accentuation, the instruments of Mr Steinway have over those of their competitors an advantage that cannot be contested. The pianist feels under his hands an action that is pliant and easy, which allows him at will to be powerful or light, vehement or graceful. These pianos are at the same time the instrument of the virtuoso, who wishes to astonish by the éclat of his execution, and of the artist, who applies his talent to the music of thought and sentiment bequeathed to us by the illustrious masters...”

|

The cantabile progressively increases, proceeding towards the high acute texture of the soprano, revealing a kind of phonic vigour, which remained typical of the Steinway pianos.

|

The purity of the transient maybe also gains advantage from the absence of resonance chords, not dampened, and added on, after the patents, mentioned before.

The action is a development of the mécanique à double percussion (double escapement action) of Sebastien Érard, perfected in a patent of Henri Herz in 1850 on the drop-screw of the second escapement, which rendered perfect the control of the pianist’s touch

.

|

The device to maintain the tension of the four master |

This instrument is also provided with a futuristic device to maintain the tension of the four master ribs of the soundboard, regulating within certain limits the arrangement of the soundboard–ribs unit.

This extraordinary historic tipology occupies a central and decisive role in the context of feverish research carried out on the piano during the nineteenth century, at the same time representing the archetype of the grand piano of today. If in the first half of this century, the most important contribution to this research came undoubtedly from the Old Continent, the most important event of the second half-century, in terms of organological history of the instrument, was without doubt the advent of the Steinway tipology.

The restoration

This grand piano came from United Kingdom: it was probably used to its limits during the height of its working life (as happens with most successful instruments), and it then suffered the most varied adventures under various circumstances, which can be easily followed from its direct analysis.

Deprived of the strings, and used as a liqueur cabinet this instrument showed numerous cracks in the soundboard due to shrinkage, and it wasn’t longer able to make any sound..

|

Flavio Ponzi’s restoration developed in two phases. In the first phase (from 1989 to 1990), he concentrated in particular on the recovery of the original soundboard and on a full restoration of the action.

It was necessary to work on the soundboard, restoring its visual and physical acoustics continuity. This goal was possible following a patient integrative “inlaying”, using thin strips of Picea Sitchensis (Bong.) Carrière, taken from a surviving parts of a Steinway soundboard that was a few years later, and which had been tracked down by chance.

How often happens with pianos so old, the original arrangement of the soundboard–ribs unit was altered from repeated thermo-hygrometric stress.

The soundboard and the ribs themselves were completely taken apart and later accurately reassembled, to allow perfect restoration of the original physical arrangement of the instrument.

This long procedure was part of the research of Flavio Ponzi on numerous other historic grand pianos, in particular for the aspects regarding the relationships between deformation of the arrangement of the soundboard–ribs unit, and the acoustic output. This physical acoustics approach in the reconstruction of the original timbre and phonic output allowed the collection of new experimental data (presented at various international congresses on study of musical instruments and acoustic physics).

The keyboard and the action of this Steinway grand piano were misshapen because of the repeated hygrothermic stress, its intense use, and its bad conservation conditions. Therefore, these parts were carefully restored or substituted by modern components in order to provide perfect efficiency for the piano interpretation.

The restitution of an optimal structure of the primary phonic system (soundboard–ribs unit) and the recovery of the full mechanical efficiency showed the great warmth of the timbre and the width of the phonic performance of this instrument.

Due to the mistreatment suffered by the body/case, this last was integrated (in this first phase) with parts that were recovered from coeval Steinway pianos.

During that first restoration were reused the original hammers, yet somewhat worn and thinned, as it does in most historical pianos.

The instrument was used by Flavio Ponzi for the recording of a CD of music of Brahms (1990), and in the following years, numerous pianists played it during concerts.

Over the next 20 years, Flavio Ponzi reached numerous experimental objectives concerning the restoration of historic grand pianos, and he returned to [the second phase of] this restoration during 2010 and 2011, completing some aspects that had not been approached entirely during the first, complex, phase.

1. The complete remaking of the elegant body of the instrument, in original neo-Rococo style.

2. The replica of the hammers;

|

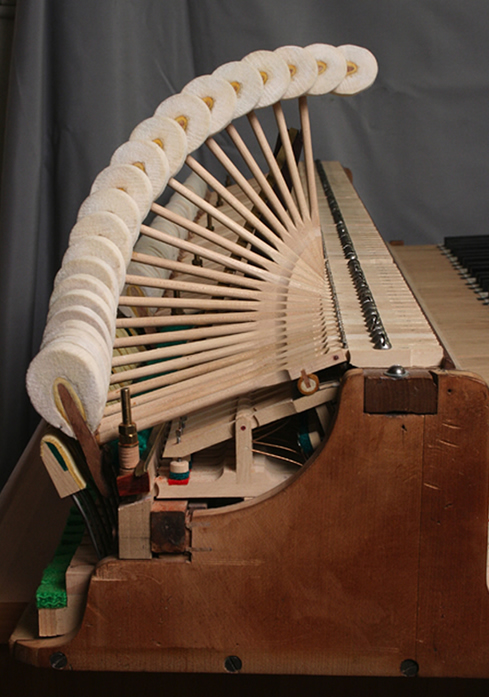

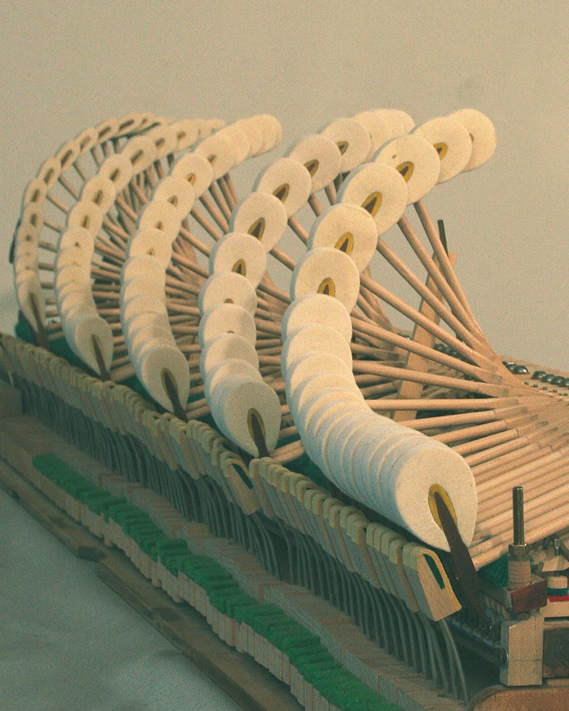

Remade low hammers |

3. The re-felting of the original hammers;

4. The complete restoration of the original wrest-plank (pinblock).

Moreover, a complete restoration of the original elegant body of the instrument was carried out, which had been covered in layers of ‘pirate’ varnish. This complete restoration was based on comparisons with original coeval Steinway models. The duplicate of the lyre and of the original legs was made in the year 2002 by the wood-carver Gianfranco Grandoni. The overall result shows multiform chromatic exchange between various noble woods:

Brazilian rosewood for the body of the instrument, Indian hard rosewood and ebony.

The restoration then confronted the central problem of the marked wearing of the hammers, and consequently the need for definitive restoration of the original timbre physiognomy of this instrument. Therefore, was made before a complete replica of new hammers, and afterwards the re-felting of the original (hammers), following the methodology detailed by Ponzi for the restoration and the interpretative recovery of the piano typologies of the Romantic period. This approach is based on an objective physical acoustics assessment of the results of the restoration, with the aim of avoiding discretional and subjective judgement (otherwise known as auto-referencing) of the restorer himself. This duplicate set of hammers was produced on the basis of the observation and study on the measures, the materials and the assembly routines, of three Steinway hammer sets of the same period (from 1867 to 1880).

The re-felting process of the original hammers, was a moment of disciplinary and technological synthesis, as part of the extensive research carried out by F.Ponzi on the Steinway hammers of the second mid-nineteenth century.

This research has clarified in a new way some crucial differences constructive and aesthetic between Steinway hammers of late-romantic period and the modern ones.

Now Flavio Ponzi is being preparating the elaboration of scientific articles on the disciplinary and aesthetic results obtained, including through the acquisition of numerous acoustic samples, which allow to verify the sound in relation to some subtle variables applied to the replica and to the re-felting of the piano's hammers.

Below: some original hammers of the instrument, from no. 6 to no. 10 (from right to left). Before (above), and after the re-felting process (below), performed by F.Ponzi with its own special-purpose equipment. The picture documents the form not yet normalized, visible afterwards the separation of the hammers. |

|

Below: the entire set of the re-felted hammers, very near to the definitive form and voicing. The progressive numeric order of the hammers goes from right to left. The re-felting has also involved the rebuilding of the under felts (in bad conditions), from the hammer n. 38 to the n. 85. |

|

Considering the good gluing of the felts, F.P. has preferred to not apply the safety clip, in order to not weaken the original hearts of the hammers (made of mahogany) with a further hole. It's to consider that in these hearts of wood (of the hammers), the builder had made from the beginning two holes (of about 1 mm.), to apply the typical knots of reinforcement made with copper wire, used in the Nineteenth century. Below: the original hammers re-felted, after the mounting on a second bar, expressly made, complete of the hammer-shanks and of the regulators of the first escapement. At the left of the keyboard you can see the set of the remade hammers. |

|

Below: particular of the original hig hammers re-felted |

Below: overview of the original hammers re-felted |

|

|

| So this instrument has two sets of hammers perfectly in working order: the first of the original hammers re-felted, and the second of the hammers remade. This is warranty for a new and very long efficiency of this grand-piano. The voicing of the original hammers re-felted , is perfected from F.P. playing the piano during some weeks, in order to verify the completeness and the amplitude of the expressive nuances, and of the dynamic range. These ancient hammers (re-felted with the original procedures), have shown at once an expressive and very pure sound. |

|

Below: images of the wrest-pins [tuning pins], of 6,75 x 64 mm. The friction, measured anticlockwise with a dynamometer, goes from about 17 to 21 Nm |

|

|

Below: remade high hammers |

|

Below: remade low hammers |

|

Below: some views of the piano |

|

Below: inside view of the action |

|

Below: top view of the piano |

|